Installation view of Black Prairie Septet from Paul Stephen Benjamin: Black of Night, 2024. On view at Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, May 18-September 15, 2024. Courtesy of Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts. Photography by Colin Conces.

The Land Next time

by Derrick Woods-Morrow | Antennae #60 Earthly Surfacing

Who owns land and by what means? Derrick Woods-Morrow’s The Sand is Ours compiles an archive of reflections during a summer on Fire Island – a cascading paradise of boardwalks, utopian ideals like no other, romantic hope for inclusionary spaces – none of which actually exist. The boardwalks are broken, the utopia is dystopian. And so, the work developed within The Sand is Ours focuses on struggling to locate a sense of selfhood, a community voice, and a way of being beyond those expectations.

text and images: Derrick Woods-Morrow

Recalling the classical contrast between praxis (or work on the self) and poi-

esis (or work in the world), the critical poetics of afro-fabulation... can be well

thought of in the performative sense of a doing.

But what do the blank spaces in discourse do, exactly?

Tavia Nyong’o, Afro-Fabulations: The Queer Drama of Black Life (conclusion)

[on genocide and slavery] ...Their force is particular yet like liquid, as they can

spill and seep into the spaces that we

carve out as bound off and untouched by the other.”2

Tiffany Lethabo King, The Black Shoals (introduction)

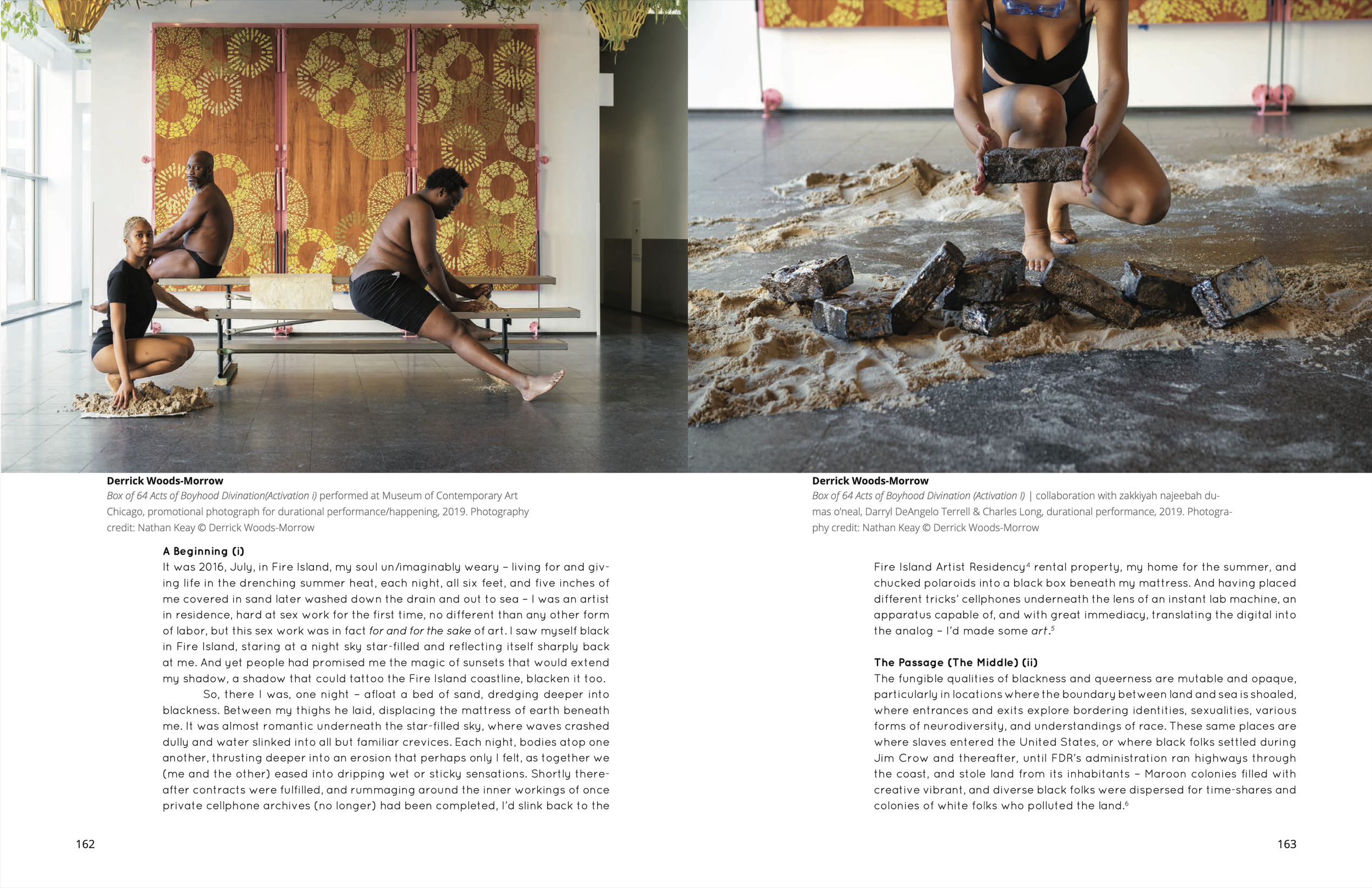

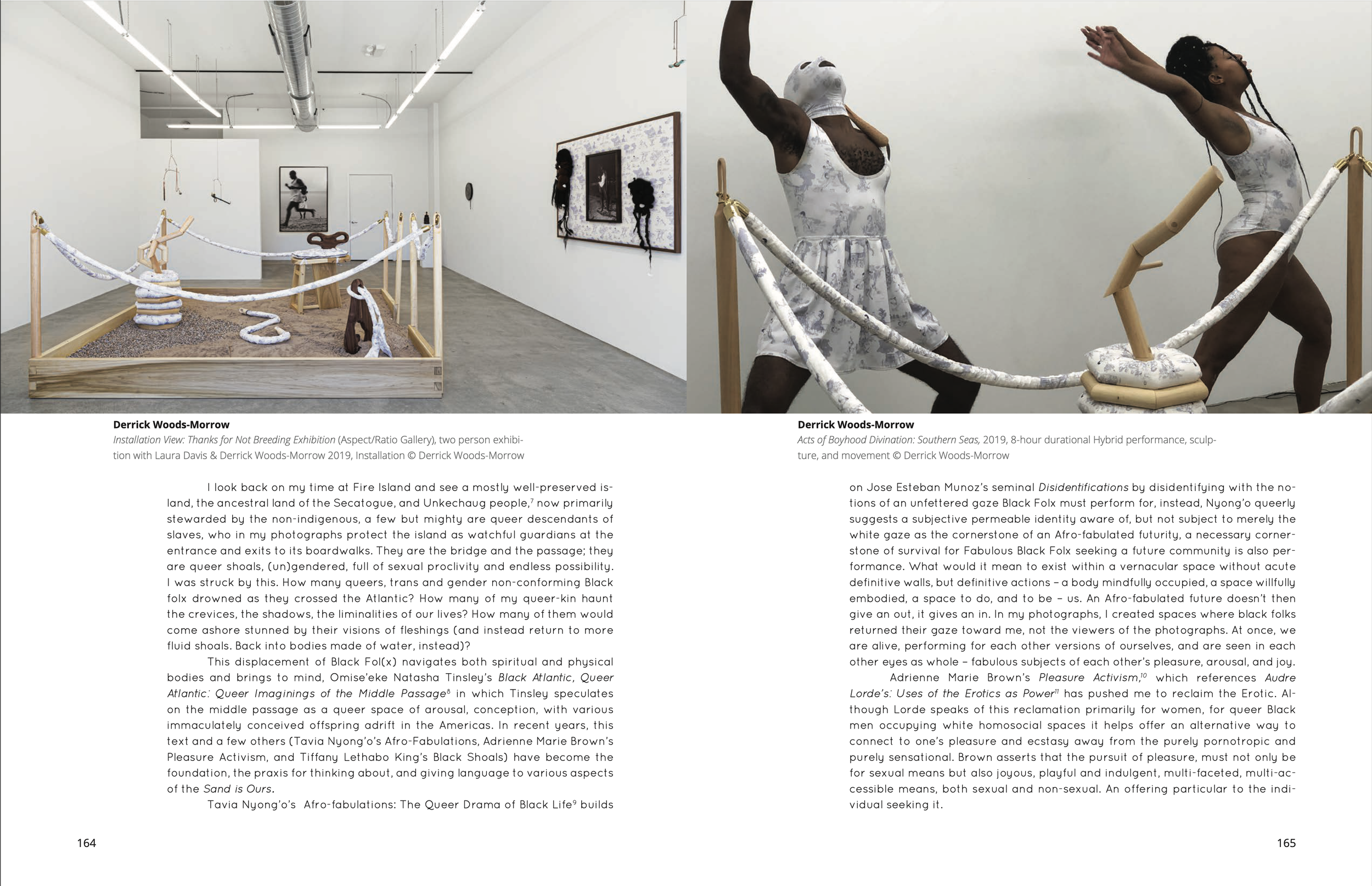

The Sand is Ours originated as a performance-based reclamation project where at once: (i) - I had sex with various men in Fire Island in 2016, tautologically bound by contract in a New York State, then and now, lacking in protection for sex workers. I initiated contact with the others on the beach, in various bars, and through the application Grindr, and proposed sex (in all its varieties) in exchange for access to their cellphones and the ability to use their personal images in my work – the resulting body of work debuted in the solo exhibition The Sand is Ours (2017) held at the Lesley University Gallery. (ii) - I documented the various BIPOC fol(x) occupying Fire Island during the summers of 2016 - 2019. This practice continued for 4 years until the Covid-19 pandemic stopped me from traveling in an attempt to stay safe. (iii) - I collaborated with other Queer Folx of Color as we mailed thousands of pounds of sand from the Fire Island Meat Rack to the front steps of my studio on the Northside of Chicago. Furthermore, we co-authored ethnographic-centered performances in museums and galleries as art happenings that stretched between Chicago and Fire Island. This practice continued until 2019, when I was blacklisted by the USPS for sending sand coming from the National Park Service FIMI project to myself.

antennae: THE JOURNAL OF NATURE IN VISUAL CULTURE - ‘earthly surfacing’ ISSUE 60 - SPRING 2024

Petrichor, an exhibition label text for Paul Stephen Benjamin’s Black Flag (In Memory of Malcolm and Betty), 2024

Petrichor or the aroma of pavement freshly softened by rain. A bit like the smell of fresh tears, and engineering fluid. It's a phenomenon that brings me to the space between the body & ground. The distance seems ever present, in how we walk, and how we move. Pressure. Against the pavement some bodies have felt, skinned a knee, grazed by a bullet. Pressure. The same pressure of protests, of igniting a framework for liberation. Pressure eased by freedom, not a flag. Sometimes neighborhoods are so large it rains only in one section. As if perhaps tears drape one block at a time. In a moment of tragedy there is a moment of protest. In a moment of protest, there is the potential for something else. Paul Stephen Benjamin knows that our cascading bodies leak with engineering fluid, a procession across the room, and into commonplace. A flag raised to the sweetness of flowers given after new rain and residing in the same commons as Malcolm and Betty. As if to begin a sentence with “Dear Black man — Dear Black woman”

-Derrick Woods-Morrow (with TK Smith on the mind) for Paul Stephen Benjamin: Black of Night, Bemis Center

Installation view of Black Suns from Paul Stephen Benjamin: Black of Night, 2024. On view at Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, May 18-September 15, 2024. Courtesy of Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts. Photography by Colin Conces.

Installation of Paul Stephen Benjamin: Black of Night, 2024. On view at Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, May 18-September 15, 2024. Courtesy of Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts. Photography by Colin Conces.

Over the last month I’ve spent time on multiple devices, using multiple strategies to catch up with the now scattered members of Concerned Black Image makers (CBIM). And as a national pandemic overwhelms the USA this interview connects the dots of Black voices who are creating new images for seeing ourselves doing blackity-black things, despite the pressure we feel from a world that consistently values our cultural production, but not us; the makers, who are engineering American culture.

Still…the members of Concerned Black Image Makers (CBIM), a Chicago based photography collective of founders Zakkiya Najeebah and G’Jordan Williams, and members Maya Iman, Sierrah Floyd, Jamillah Hinson, Andrea Coleman, Darryl DeAngelo Terrell and myself – Derrick Woods-Morrow, have gathered throughout quarantine, if for nothing more than to laugh on Zoom calls, encourage and be real with one another via WhatsApp – occasionally spreading love by leaving each other voicemails.

In the past, a number of CBIM members have participated collaboratively in my performances, photographs, and compositions — in my work with Black Fol(x) our bodies touch each other, skin folding over, creasing, hanging and constricting around gendered garments, and around other bodies, around the expectations of what various Black people should be doing with their time together, so much of which is now a digital meditation due to Covid-19. (I haven’t made any of this work in the year 2020 for fear of putting the very people the work intends to protect and highlight at greater risk of something they are already at the greatest risk for).

Now, more than ever, I feel that ‘touch’ has become an abbreviation of the physical. A realm away from where skin meets skin. To touch base is to be on the go; is to press down keys and buttons from the safety of one’s home. To “click” and unsurprisingly to “meet” exists mostly through digital platforms such as Google, Facebook Live, Zoom calls (or the gloryhole hanging in my living room).

to keep us going,

to stay afloat in kinship,

our family abundantly chosen.

we have confided in each other,

our highs and lows,

our lack of interests in the outside world.

None of us are really present, we are all sort of AWAY.

The members of CBIM are part of a generation of makers raised on the internet. We are no strangers to the disconnection.

If we are not returning to the past, and are choosing to build a new future,

How can a group of Concerned, Black, Image Makers help us get there?